Note in this essay: artist = maker of traditional studio objects (paintings, sculpture etc)

What art is is an opinion...

an opinion that changes with time.

What the average person knows about art- from the mysterious “art world”

to rumors of murky financial deals and money laundering- is based on a

long-standing model of wealthy patrons. It’s always been consumed as a

luxury item, access limited by class and connection. These same wealthy

patrons are also supportive of “art in community” through outreach

programming in museums and schools thereby influencing how the general

public experiences art, the subject matter, and artists themselves.

This structure has not been challenged in any meaningful way that impacts

the sector’s ability to solely determine what is culturally significant, that is,

to decide what is and is not art. Right now, though, independent artists and

their patrons are part of a moment bringing new meaning to the words

“public artist.”

A business that began in the great houses of Europe then in burgeoning high

society in the US, art has essentially been their domain to define and expand

into a full-fledged international industrial complex complete with

conglomerate galleries and trading on the stock exchange. A proliferation of

themes, independent curators, fairs and the potential for fast money in the

market over the last thirty years began driving the direction of what art gets

made as well as the course of art history.

Focused on a coterie of celebrity artists best representing what they consider

to be investment quality art, galleries and dealers are no longer showing a

cross section of the myriad ways artists explore media. Identity art is

popular as it proves the canon has diversified by including an array of artists

who are not white men.

In a symbiotic relationship, dealers rely on museums to create value for

artists they represent and collectors with interest in adding value to their

holdings sit on museum boards. They continue to decide what is culturally

significant and how we talk about it. It is a clear conflict of interest when

museums exist in public space and purport to be repositories for all cultures

when they have started to depend on commercial enterprise to evaluate the

impact and importance of human creativity.

It’s worrisome that galleries and dealers are now producing catalogues and

films about artists and that critics, looked upon as impartial, have lost the

power enjoyed by someone like Clement Greenberg to sway the course of

art. It’s worrisome when a representative from the Middle East Institute

assures her PBS audience the artists from the Middle East in her exhibition

speak “the same art language we do,” reflecting centuries old belief that the

art that matters is western in concept and execution.

In the middle of the 19th century with rising popularity of the photograph,

what had been a skill-based studio business documenting and decorating the

lives of the rich and famous reinvented itself. It began by creating a

distinction between what they sold, “fine art,” and other decorative products.

Instead of portrait, landscape and other types of commissions, they turned

to the buying and reselling of goods.

This pivot allowed for more diversity in the ways that artists worked and it

established the gallery and dealer to act on artists’ behalf because then, like

now, unless you were born into a wealthy family or had connections, you

needed to be “introduced” by someone who “mattered.”

Someone like Van Gogh painting away in his studio is the image conjured in

most minds by the word artist. What is not pictured- aesthetic, historic or

pictorial research; preparing the work for documentation, exhibition and

storage; cataloguing, marketing, promoting and selling- complete the artist’

job description.

Jean Michel Basquiat’s short and tragic career began because of a

serendipitous meeting with Andy Warhol on the streets of New York. His

guerilla entree into a milieu he would have a hard time breaching otherwise

led to an explosive presence that ended with a heroin overdose and a

questionable body of work unlike any paintings seen before. When he died,

museums refused gifts of his work- now, by their own metric (auction sales),

he is one of the most important artists of the 20th century. History shows

Basquiat did what he had to do.

For Sam Gilliam that meant and still means being at the top of his studio

game. Language pared to the barest elements of color and shape, he’s

reaching a pinnacle after a lifelong exploration of painting in three

dimensions that started with structured draping and wound its way to an

elegant fabricated form. He has yet to be acknowledged for his contributions

to the field of painting.

With a beginning as auspicious as he experienced, you would think an artist

of his caliber would have been celebrated in the art world his whole career

but it is only in the last couple of years that Gilliam has been represented by

top tier galleries, i.e., the people deciding which artists are important and

what art is culturally significant.

That many artists practice outside these parameters and are consistently

making a comfortable living making new work needs more visibility. Many

are not rich or famous yet sustain a successful practice producing and selling

work that for whatever reason does not resonate with the “art world.”

It is a popular fiction that success as a fine artist can only be found

participating in the traditional art market with its well documented history of

sexism, racism, ageism, misogyny and exploitation. Because of its elite

origins and operating structure, art is rarely thought of as an industry and

artists are not seen as the common laborers found in other professions.

Most spend years in the field with little to show for their hard work because

it has been difficult to direct a practice to the attention of the general public

without gallery representation and remain in contention for museum

exhibitions and collections.

The art world that we read about in mainstream media and that we talk

about when we talk about buying and selling art is exclusive to a very

wealthy group of people. Great monetary values don’t always equal great

cultural value except to this very wealthy group buying and selling what

THEY DECIDE is art. In 2020 that included a questionable Leonardo da Vinci

and the first AI-generated painting auctioned at Christies for more than

$400,000. In 2021, it included non-fungible tokens and fully embracing the

new media and technology, eliminated a need to trade for physical objects.

Dialogues about cultural diversity, inclusion and an expanding art public

suggest this needs to change. Contemporary arts marketing acknowledges

new potential buyers outside this realm and targets a more diverse base

with disposable income to introduce to collecting.

Outreach by museums in neighborhoods and schools has resulted in a bigger

and still growing art appreciating public. If an artist’ goal is to sustain

practice through the sale of objects, this is a demographic to seek out and

cultivate. One way this happens is placing galleries representing artists and

artists representing themselves selling in the same venue.

Precedents include the bi-annual National Black Arts Festival in Atlanta first

held in 1988 and the New York art fair, Art Off the Main, organized by Loris

Crawford presenting artists and galleries of African descent beginning in

2004. One such current venture is the SuperFine national network of six

fairs featuring galleries and artists representing themselves.

In the 21st Century, artists have finally understood the importance of self-promotion

and can create new career paths by building personal audiences

with the tools available to promote and sell to a general public trained to

appreciate art by museums in the community and school outreach

programming mentioned earlier.

When artists practice outside the traditional boundaries, they erode a tightly

held control over the entire industry by unlimiting what work is available. It

increases the likelihood that artists will make the work they want to make

without regard for viability in the art market and challenges the art world to

be more stringent in the work it chooses to champion.

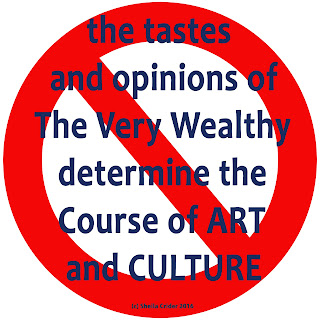

We live in an age when the course of art and culture does not have to reflect

the tastes and opinions of the very wealthy.

Open engagement with the public permits artists to build a constituency of

supporters that will follow the artist’s career with interest and insight into

what making art really means. This consistent exposure over time gives the

public agency to decide who can be an artist and what “fine” art is, the same

way it has been decided exclusively by the art world in the past.

Artists targeting the general public may seem of little consequence but like

all artists’ movements, the changes it brings will be absorbed and

incorporated into the machine soon enough and the business of art will plod

along albeit with one important change: more people participating in the act

of identifying and preserving art and culture.

(in memory of Stevens Jay Carter 1958-2021)

No comments:

Post a Comment